How the 1989 British and Irish tourists put Australia on the map

And to think there were those who considered a Lions tour of Australia was not a proper tour in the way trips to New Zealand and South Africa had been, those body-battering, lung-busting, drawn-out expeditions of folklore. Willie John McBride had grave reservations. So, too, did JPR Williams. “These are not real Lions,” said a man who had given blood and scar tissue to the cause himself.

That is the context for the first full tour of Australia that set out from the British Isles in the early summer of 1989. You could see the critics’ point. Australia had always been considered a stopping-off point on the way to the real thing in New Zealand. This year the British and Irish Lions will play Argentina in Dublin as a warm-up act. Back then it was Australia and onwards.

The great tours of New Zealand and South Africa (in the seventies in particular) had been epic adventures, in scale and dramatic content, rugby’s equivalent of a medieval crusade. There were 26 matches in New Zealand (and Australia) in 1971, 22 in South Africa in 1974. And Australia in 1989? Twelve matches, six fewer than the previous lowest. And with fixtures against the B teams of Queensland and New South Wales. No Canterbury or Transvaal on this fixture list. Yes, you could see why there might be grumbles and scepticism.

And yet it is not outlandish to say the 1989 tour was the saving of the Lions. It is not wrong to claim, either, it cemented the status of Australia as a bona fide one-stop place to tour. (It’s also not daft to state the Lions proved the sort of testing opposition for the Wallabies that sent them on their way to being world champions two years later.) Yes, it was a seminal event in so many ways.

The Test series gave us great theatre, unexpected twists and turns, crazy cock-up tries as well as sublime cameos of genius. Oh, and massive punch-ups for those of us still with atavistic inclinations. It had the lot. By the time the tourists headed home with the first Lions series victory in 15 years, becoming the first Lions team also to recover from a 1-0 deficit, there were no longer any naysayers. Australia was a fit and proper place for a Lions series – remember, too, South Africa were (rightly) still excluded from the international arena – and, indeed, was to provide series in 2001 and 2013 which replicated this one for edge and spectacle and controversy. If the 2025 tour follows suit then we are all in for a treat. Dust down those headlines.

There is a devilish contradiction at the heart of the Lions. The fans love it. The players love it too. And yet there are still those, sadly many of them in high office in the game, who see the tours as an indulgence. They cost money. They put strain on player welfare needs. Yet the very fact all these challenges lie in their way is the very reason they should exist. It was the same in 1989, if for different reasons with South Africa ostracised and many wondering what was the point.

Ian McGeechan recognised all these obstacles and drawbacks. Yet he relished the challenge, even as a teacher taking unpaid leave and trying to make ends meet. Manager, Clive Rowlands, hoodwinked Geech into driving down from his home in Leeds with wife, Judy, to Tenby in Pembrokeshire for a supposed pre-tour Lions selection meeting only to present him with a much-needed short break before hostilities began. All within the amateur regulations, you understand.

McGeechan went out on a limb with the uncapped Guscott, the first to recognise in him what were to become trademark traits – an ability to see things others couldn’t and having the nerve as well as the physical attributes to make them happen.

There was precious little budget in those times (the daily tour allowance was £1.25). There was hardly any back-up resources either. The management was only five-strong: Rowlands, McGeechan with Roger Uttley as assistant, Dr Ben Gilfeather and physio, Kevin ‘Smurph’ Murphy. It was a far cry from the 30-plus backroom staff of Clive Woodward in 2005 or the glitzy, showbiz backdrop the 2025 Lions will have when their captain and squad is announced in London on 8th May.

Selection was a committee affair in 1989 although Rowlands assured McGeechan his voice as coach would be the loudest and he would be guaranteed two unquestioned picks of his own. One of those was to be Jeremy Guscott. That didn’t turn out too badly, did it?

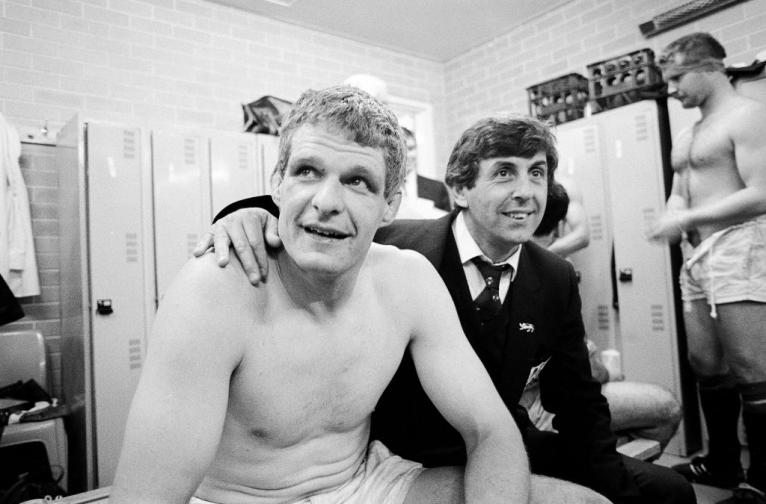

Finlay Calder was McGeechan’s captain, a flinty Scot, a man of his own mind as he showed during that tour when he stood in front of the squad after the first Test debacle and acknowledged Andy Robinson had every right to be considered in his place on the flank. Calder may not have been without flaws as an openside but he stands alongside all those others, the McBrides and the Johnsons and the Warburtons, who have led the Lions with distinction.

England skipper, Will Carling, had some sort of claim to the captaincy but it was only right coach and captain should be on the same wavelength. You never felt that really happened with McGeechan and Carling, not in 1989 nor in New Zealand four years later when Gavin Hastings was preferred despite Carling by then having two Grand Slams to his name. Carling was to withdraw from 1989 consideration with a shin splints injury. You wonder if he looks back on his Lions ‘career’ with regrets.

There was to be no such feeling about the new wunderkind of English rugby, Guscott. McGeechan went out on a limb with the uncapped centre, the first to recognise in him what were to become trademark traits – an ability to see things others couldn’t and having the nerve as well as the physical attributes to make them happen.

The one legitimate charge against a Lions tour to Australia is the quality of the non-Test opposition. The Lions need to be tested if they are to sort out their own selection and get them in the groove. The 1989 Lions thought they were ready. They were not. Even allowing for being undercooked, they still performed woefully in losing the first Test, 30-12, Australia outscoring them four tries to nil. It was a sobering moment. Yet also a revelatory one. Even in the gloom of defeat, McGeechan felt he had seen where the Wallabies might be vulnerable – up front.

Few others could have seen it, particularly as it had been the wondrous tactical kicking of Michael Lynagh that had tormented the Lions at the Sydney Football Stadium, a venue packed to its 40,000 rafters, a remarkable attendance for Australia where Aussie rules and rugby league dominated the sporting agenda. Only two years earlier, Australia had failed to fill the Concord Oval for a World Cup semi-final against France despite being co-hosts. Only the Lions can do this.

McGeechan may have had his masterplan. He had little time to put it into practice before the second Test at Ballymore in Brisbane seven days later. There is never enough time on Lions tours. That is their beauty. The coach and the players have to sort it out between them.

McGeechan can hardly be considered rugby’s Don King, the boxing matchmaker revving up the stakes at every turn, but the Scotsman knew what was on the line – the very future of the Lions if they lost.

Geech as well as Providence did the trick. ‘Iron’ Mike Teague had missed the first Test through injury. In he came, as did lock, Wade Dooley, in place of line-out master, Robert Norster. It was a tough call on Norster but the right one. McGeechan wanted his Lions pack on the front foot, by any means available.

Rob Andrew, who only arrived on tour after Ireland’s Paul Dean was injured in the opening game in Perth, replaced Craig Chalmers. And in came Guscott after a promising showing in the midweek game against ACT in Canberra to form a centre partnership with fit-again Scott Hastings.

And so, the red-shirted warriors for what was to be dubbed the Battle of Ballymore, were primed to get in amongst the Wallabies. McGeechan can hardly be considered rugby’s Don King, the boxing matchmaker revving up the stakes at every turn, but the Scotsman knew what was on the line – the very future of the Lions if they lost.

The forwards would do their own thing, as indeed they did. McGeechan had more subtle plans. Well, sort of. He encouraged scrum-half Robert Jones to hassle and harry his opposite number, Nick Farr-Jones, Geech taking his cue from how his former team-mate Dougie Morgan had once managed to hound the great Gareth Edwards to distraction at Murrayfield.

Jones was crucial to the Lions’ strategy in another way, for the control he was to exert and to bring the backs into play. On the day before the Test, McGeechan, Uttley and Jones took themselves off to Ballymore on their own, covering virtually every blade of grass at the quaint old stadium, running through every possible scenario. Sports psychologists were later to make fortunes outlining the theory of visualisation, taking years to graduate. McGeechan got there before them and took about an hour.

Geech couldn’t have planned it better. Jones trod on Farr-Jones’ foot at the first put-in and the two bantamweights went at it hammer and tongs. The forwards needed no second bidding. Even so, the Wallabies were hard to shake off and even led, 12-9, until the closing stages before tries from Gavin Hastings and Guscott got due reward for the Lions’ efforts to close it out at 19-12.

“Beaten up by English coppers,” said Wallaby coach, Bob Dwyer, in reference to three serving policemen in Lions’ ranks, Wade Dooley, Paul Ackford and Dean Richards.

The Aussies didn’t take kindly to defeat. “Beaten up by English coppers,” said Wallaby coach, Bob Dwyer, in reference to three serving policemen in Lions’ ranks, Dooley, Paul Ackford and Dean Richards. One newspaper pundit wrote Australians ought not to be surprised by the brutality of this trio as it would be no more than they would be doing in a Friday night shift in the back streets of Derby. Charming.

The sour-grapes whingeing was music to the ears of the Lions themselves even if McGeechan did reprimand his young Welsh prop, Dai Young, for a flagrant kick to the head on Wallaby Steve Cutler. The rebuke was delivered behind closed doors. Front of house, the Lions stood their ground.

It was a broiling backdrop to the third Test although two emissaries, McGeechan and one of rugby’s greatest ever men, Wallaby assistant coach Bob Templeton, did meet for off-the-record peace talks. And even a tipple.

The series decider back in Sydney was less violent but no less intense. Again, it was close with the contest settled by the pressure exerted by the Lions and the blooper by David Campese it induced, the Wallaby wing chucking a suicide pass to his full-back, Greg Martin. It fell to the turf behind the goal line and Ieuan Evans pounced. The winning score is the stuff of legend, Guscott, poised and fearless, dinking the ball between two defenders, re-gathering and scoring under the posts. It finished 19-18 and history was made.

The Lions were back in business and Australia was on the map.